2022 was the Earth’s hottest year…so how is there STILL climate inaction?

Despite the hard science proving climate change, there is a persistent portion of the population who negate this to an extent. Some deny it is happening, some think it is conspiracy and some think the solution is worse than the reality. For decades, research has shone a light on climate change and the dire effects which inaction can produce, yet, why does climate change inaction and scepticism continue?

In September, Professor Matthew Hornsey from the University of Queensland, presented a guest lecture at the University of Erfurt, hosted by the Institute for Planetary Health Behaviour, titled “A toolkit for understanding and reducing inaction on climate change”. Hornsey’s research dives into this perplexing issue and importantly, what we can do about it.

In his lecture he identifies waves of climate change scepticism. Wave 1, where people deny that global temperatures are rising. Wave 2, where people admit that temperatures are indeed rising but it is not due to humans. And lastly wave 3, here people do not see climate change as very harmful. In fact, they see the solutions to combating climate change to be worse than climate change itself.

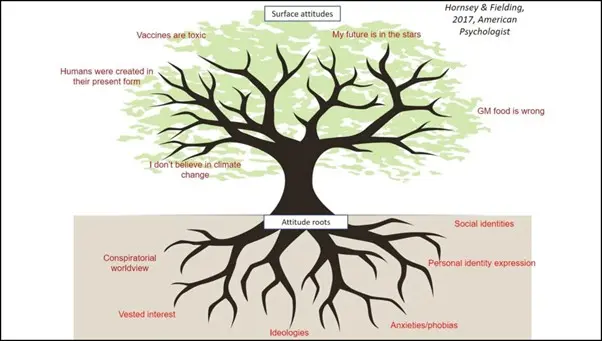

However, such climate change scepticism can also be seen as a cluster of attitudes. We can use Hornsey and Fielding’s tree metaphor to better understand this (Hornsey & Fielding, 2017)(See Image 1). A person’s behaviours and actions are the branches, they are what we see. However, the roots are most important and without them, the branches could not exist. The roots are base attitudes such as, anxieties, ideologies and personal identities. In particular, ideologies play a key role. Hornsey has been able to identify ideologies which point to a greater likelihood that a person will be a climate change sceptic. Hierarchical ideologies and ideologies of anti-big government, individual liberties and free market ideology all seem to have a correlation to levels of conspiracy theory attitudes. Such ideologies also tend to align with ideologies to those on the right of the political spectrum. In so far, that political affiliation has a strong correlation on climate change scepticism. But this has not always been the case.

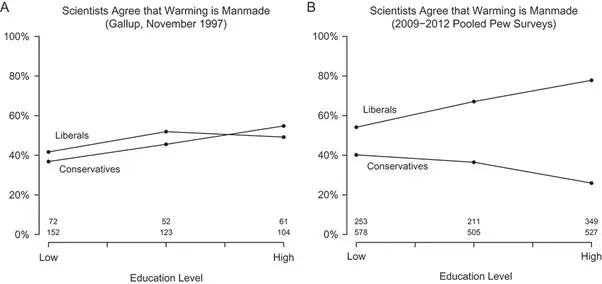

Research from a Tesler paper comparing US 1997 political belief impact on climate change scepticism to 2012 rates has shown an interesting trend (See Image 2). The 1997 research found that political belief did not impact on climate change beliefs, and the higher the level of education, the less likely to be a climate change sceptic. But the 2012 research highlighted that climate change beliefs in the US now have a political ideology root. In particular, those with conservative political ideology with higher levels of education are more likely to have climate change sceptical beliefs (Tesler, 2018). Somewhere along the way, the issue of climate change has been politicised. This trend has sadly also been seen in Australia.

Hornsey, identifies a pivotal moment in Australian politics during the Rudd led Labor government, where there was an attempt to bring in an emissions trading scheme. However, this had a huge backlash and resulted in plummeting support. When push came to shove, many of the Australian population at that time, did not want to make see the cost of living rise or make the necessary adjustments to combat climate change.

Climate change scepticism can be classified as a stream of conspiracy theory as it is the belief in misinformation (Hornsey, Biermiaczonek, Sassenberg, & Douglas, 2023). However, Hornsey identifies that climate change sceptics behave differently to other conspiracy theorists. Trends shows that if you believe one conspiracy, you are likely to believe others (Hornsey, Harris, & Fielding, 2018). But climate change sceptics don’t follow this trend. Motivated reasoning is what climate change sceptics use, consciously or unconsciously, to justify their already establish point of view. These people have already made up their minds about climate change and will then create arguments to back themselves. So much so, that research by Horney et al. has shown that even extreme weather events have little effect on climate change sceptics, as often such events are viewed as humanitarian crises. Furthermore, that scientific evidence actually has little effect on such sceptical attitudes (Hornsey, Harris, & Fielding, 2018).

So what is to be done? How can we de-politicise this issue and get everyone on board to take action? Hornsey, highlighted some key take aways. In his research with Lewandowsky, they emphasise the need to understand the context in which you are working, the approach in Australia would differ drastically to the approach in Germany. He makes it clear you need to understand a sceptics way of thinking and communicate to them in a way that would resonate with them, for example energy security or coming from a community perspective which appears to have an impact on sceptics. In this way, you are conducting persuasive ‘jiu jitsu’, looking at the underlying motivations and using that to open the conversation. However, the strongest method is to target sympathetic conservatives. It is through peer-to-peer conversation which has the best chance of success in opening a person’s eyes to the climate reality (Hornesy & Lewandowsky, 2022; Hornsey & Fielding, 2017).

But, should we be engaging in discussion with conservatives where some views can be harmful for groups of our society? The sad matter is that the earth does not have the luxury of time. People need to mobilise now to combat the spiralling negative implications of climate change. And by having these conversations there is the possibility that climate change could be de-politicised and thus, action taken. Climate change scepticism can be removed from the conservative playing hand, but this can only be done through thought-out and relatable communication. We cannot bury our heads in the sand with both camps not conversing, nothing will change if this is the case. Hornsey’s guest lecture was a realistic and refreshing view of climate change politics where attendees could reflect upon the current and dire situation we find ourselves in. It could be too easy to throw in the towel and feel hopeless about the lack of action however, Hornsey’s climate inaction toolkit provides some optimism. Myself in particular, was able to think about how I can implement some of these tips on an individual basis within work and life. Furthermore, that lines of communication between all parties must continue and it is when communication is severed that no progress can be made. The useful thing about Hornsey’s tips is that they are broadly applicable to many sectors, whether it be policy, health science or communication and had all attendees considering just how they can take small but useful steps to help combat climate inaction on a local scale.

For more information about Prof Hornsey’s research, visit his University of Queensland page at this link.

References

Hornsey, M. J., & Lewandowsky, S. (2022). A toolkit for understanding and addressing climate scepticism. Nature Human Behaviour, 6, 1454-1464.

Hornsey, M. J., & Fielding, K. S. (2017). Attitude Roots and Jiu Jitsu Persuasion: Understanding and Overcoming the Motivated Rejection of Science. American Psychologist, 72(5), 459-473.

Hornsey, M. J., Biermiaczonek, K., Sassenberg, K., & Douglas, K. M. (2023). Individual, intergroup and nation-level influences on belief in conspiracy theories. Nature Rviews Psychology, 2, 85-97.

Hornsey, M. J., Harris, E. A., & Fielding, K. S. (2018). Relationships among conspiratorial beliefs, conservatism and climate scepticism across nations. Nature Climate Change, 8, 614–620.

Tesler, M. (2018). Elite Domination of Public Doubts About Climate Change (Not Evolution). Political Communication, 35(2), 306-326.

About the Author

Alyssa McIntyre is a MPP student at the Willy Brandt School of Public Policy and the Student Assistant Editor of the Bulletin. Alyssa’s area of interest is disability related policy which stems from her previous experience in the disability services sector in Australia.

~ The views represented in this blog post do not necessarily represent those of the Brandt School. ~