Include them all: Colombia should implement a policy of gender-neutral and free Human papillomavirus -HPV- vaccination

In Colombia, the free national vaccination scheme against Human papillomavirus covers girls between 9 and 17 years old (Ministerio de Salud, 2023) but not boys. Parents cannot afford the vaccine’s costs for boys because these are costly. This creates a barrier that has left males unprotected as they cannot access the vaccine. This past August, the National Immunization Practices Committee voted in favor of extending the free coverage to males. This is something to celebrate, as the strategy of gender-neutral vaccination can be the most effective way to protect males and females and eliminate the burden of women as the only ones responsible for prevention.

What does current scientific evidence suggest about men’s HPV virus transmission, effects, and vaccination?

According to the World Health Organization, the Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) is a widespread virus that can cause various diseases, including cancers, in both men and women. It spreads through sexual contact and can lead to cervical cancer in women and cancers of the neck, head, anus, and throat in both genders (2022). HPV infections can persist for up to 24 months without symptoms, facilitating its spread, particularly, because some people don’t develop any symptoms. To date, there are 6 HPV vaccines approved for women, and 3 of them -Cervarix, Gardasil, and Cervavax- for men. These vaccines are recommended to be administrated in two or three doses, before the start of a sexually active life. According to the WHO position, HPV vaccines increase the immune response to this infection for at least 12 years, offering a high level of protection against the different kinds of cancers described above (2022).

The costly barriers to HPV vaccination access for boys

In Colombia, there is a national vaccination scheme against HVP that covers two to three doses for girls between 9 and 17 years old (Ministerio de Salud, 2023). However, male children can be vaccinated but parents must pay for it.

The complete scheme costs between 80 and 100 USD, depending on the health provider. Even with the lowest price, the current costs of the HPV vaccine are prohibitive because the country’s monthly minimum wage is around 242 USD. In 2021, 39.3% of the population was living in monetary poverty with a monthly income equivalent to 72 USD, and 12.2% in extreme poverty with an income equivalent to 33 USD (DANE 2021, DANE 2022). With this income and deprivation of rights, families cannot prioritize vaccinating their children because they cannot afford it.

Gender-neutral vaccination and the inclusion of boys in HPV vaccines promote gender equality

Investigations show that there has been an over-identification of HPV as a female-specific disease, and consequently, the feminization of HPV and HPV vaccines. Feminization of the problem comes with the target of women as the vulnerable group, generating power and gender inequalities. Feminization happens when the construction of a social problem focuses just on females leaving aside males, although they are key to the problem and solution (Daley et al., 2017). This happened as well with contraception where financially, emotionally, and physically women have taken the burden, and culturally the exclusion of males has been normalized.

Indeed, with HPV and the vaccines, the focus has been mainly on cervical cancer, which is one of the important issues that came with HPV but not the only one. Women have been selected as the most responsible for HPV infection and its related illnesses, and thus, the ones in charge of prevention, leaving aside the responsibility for the spread of the virus in men. This approach also leaves aside the specific health issues that men can develop from the virus and the benefits that they can obtain from the vaccine. It is estimated that almost 85% of women and 91% of men with at least one sexual partner from the opposite sex will develop HPV infection during their lifetime (Chesson et al., 2014). Moreover, men are very likely to be recipients and transmit the virus, making HPV, a non-gender-specific infection.

42 countries and 5 from the region have included boys' HPV vaccination in their regular schemes

The WHO has identified that the level of vaccination around the globe is still challenging: 122 (64%) countries have introduced the vaccine for girls and 47 (24%) for boys (2023). These countries introduced male vaccination because the vaccination of girls did not offer enough effective protection for males. Additionally, keeping the vaccine just for girls did not protect men who have sex with men, and this strategy seems less resilient against drops in vaccine acceptance in comparison to a gender-neutral vaccination policy. Lastly, vaccinating boys and girls was likely to be more effective in reducing the circulation of the virus in the population, even if the level of vaccine acceptance was low (Colzani et al., 2021).

Studies about the countries that have implemented a gender-neutral HPV vaccination conclude that there is a reduction in HPV infections and a decrease in the cases of anogenital warts in non-vaccinated females and males. These effects are present in countries with low and high vaccine coverage, demonstrating broader herd protection (Wang et al., 2022).

In Latin America, 5 countries are also including boys as targets of the HPV vaccine. Up to this date Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Panamá, and Uruguay are the ones leading this strategy. These countries share demographic, cultural, and economic characteristics with Colombia.

Vaccinating boys is cost-effective when the HPV vaccination of girls is low

Gender-neutral vaccination of boys and girls between 9 and 14 years, could lead in the first year to a 90–96% reduction in the most common and risky kind of HPV, but this percentage will remain between 50 and 87% if the approach is just to girls (Drolet et al., 2021).

The current position of the WHO states that in low-income countries vaccinating just pre-adolescent girls is cost-effective for cervical cancer prevention, considering that the resources to prevent this cancer are limited. Critics of this position indicate that the models that have arrived at these conclusions have based the value of vaccination only upon one gender, and assuming high female vaccine coverage (Daley et al., 2017).

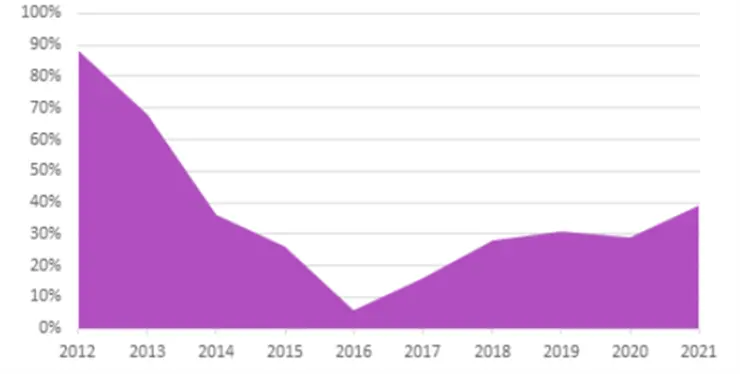

This last assumption on high female vaccine coverage to justify better cost-effectiveness in vaccinating just girls contradicts Colombian reality. Since 2014, due to an incident of health issues of girls and even after the Ministry of Health conducted investigations that confirmed that this vaccine was not a causal factor, vaccinations dropped considerably. For instance, in 2013 and 2014 the first-dose vaccine rates were between 68% and 88%, but in 2016 this rate decreased to 6%. After 2017, the rates are slowly increasing but up to 2021, the vaccination rate was 39% (World Health Organization, 2023). We can see this behavior in the graph below (Figure 1).

References

Bruni, L., Diaz, M., Castellsagué, X., Ferrer, E., Bosch, F. X., & Sanjosé, S. de (2010). Cervical human papillomavirus prevalence in 5 continents: Meta-analysis of 1 million women with normal cytological findings. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 202(12), 1789–1799. doi.org/10.1086/657321

Colzani, E., Johansen, K., Johnson, H., & Pastore Celentano, L. (2021). Human papillomavirus vaccination in the European Union/European Economic Area and globally: A moral dilemma., 26(50). doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.50.2001659

Daley, E. M., Vamos, C. A., Thompson, E. L., Zimet, G. D., Rosberger, Z., Merrell, L., & Kline, N. S. (2017). The feminization of HPV: How science, politics, economics, and gender norms shaped U.S. Hpv vaccine implementation. Papillomavirus Research (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 3, 142–148. doi.org/10.1016/j.pvr.2017.04.004

Departamento Nacional de Estadistica -2021-. (2022). Pobreza monetaria y pobreza monetaria extrema. www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/pobreza-y-condiciones-de-vida/pobreza-monetaria

Giuliano, A. R., Viscidi, R., Torres, B. N., Ingles, D. J., Sudenga, S. L., Villa, L. L., Baggio, M. L., Abrahamsen, M., Quiterio, M., Salmeron, J., & Lazcano-Ponce, E. (2015). Seroconversion Following Anal and Genital HPV Infection in Men: The HIM Study. Papillomavirus Research (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 1, 109–115. doi.org/10.1016/j.pvr.2015.06.007

Ministerio de Salud. (2023). Vacuna contra el cáncer de cuello uterino. www.minsalud.gov.co/salud/publica/Vacunacion/Paginas/ABC-de-la-vacuna-contra-el-cancer-cuello-uterino.aspx

Wang, W. V., Kothari, S., Skufca, J., Giuliano, A. R., Sundström, K., Nygård, M., Koro, C., Baay, M., Verstraeten, T., Luxembourg, A., Saah, A. J., & Garland, S. M. (2022). Real-world impact and effectiveness of the quadrivalent HPV vaccine: An updated systematic literature review. Expert Review of Vaccines, 21(12), 1799–1817. doi.org/10.1080/14760584.2022.2129615

World Health Organization (2022). Human papillomavirus vaccines: WHO position paper (2022 update), 50, 645–672. www.who.int/wer

World Health Organization. (2023). Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination coverage. publications.iadb.org/publications/english/viewer/Behavioral-Economics-Toolkit-The-Case-of-HPV-Vaccination-in-Colombia.pdf

About the Author

Nancy Apraez is a second-year student at the Willy Brandt School. She has a bachelor’s degree in law and has worked in the legislative branch in Colombia. She is interested in Conflict Studies and Development.

~ The views represented in this blog post do not necessarily represent those of the Brandt School. ~