Making Room for Age of Sexual Consent

In an article by Suresh (2022), the author brought up a case in 2017 in the state of Karnataka, where a 17-year-old girl eloped with a boy. The girl’s parents filed a case under the Protection of Children from Sexual Offenses (POCSO) with a rape allegation against the boy. When the girl turned 18 years old, the couple got married and now have two children. The husband had been acquitted of the rape charge by the lower court, however, in November 2022, the Karnataka High Court heard an appeal challenging this acquittal. The bench stressed that “consent even by a girl of 16 years and above would have to be considered” in such cases. Furthermore, the court observed that an increasing number of cases are being filed under the POCSO Act, which does not recognize consensual sex between adolescents below the age of 18.

India enacted the Protection of Children from Sexual Offenses (POCSO) Act in 2012, which provided the country with a much-needed comprehensive child sexual abuse law (Renu & Chopra, 2019). The Act addresses a range of abuse and assaults against children are defined including sexual harassment in terms of sexual comments, sexual assault, and pornographic use in front of or of the child. The law also ensures the child’s best interest throughout the entire judicial process (Anchan et al., 2021). Yet, the law turned out to deprive teenagers of much-needed sex education and health support, when they most needed it.

The gender-neutral POCSO Act made the age of sexual consent 18 years old (Pitre & Lingam, 2022) for all genders in 2013, raising it from the previous age of sexual consent of 16 years for girls only. The law also legally mandates any adult, including private citizens, doctors, counsellors, and parents, to report any offense committed under the Act. Failing to report can lead to incrimination, fines and/or imprisonment (Pitre & Lingam, 2022).

The increase in the age of consent, aligning with the mandatory reporting clause, essentially criminalizes any form of developmentally normal consensual sexual curiosity and exploration by teenagers as well as denying them a right to confidentiality. Hence, a law without any exceptions and nuances to make space for the most developmentally dynamic growth period of humans, shirks the responsibility to uphold the rights of children and youth, under the guise of protection.

Globally, many countries have adopted the legal age of marriage as 18 years. These efforts have been lauded by the international community as we move towards a gender-equitable society. Many governments, including India, however, moved to make the age of sexual consent the same as the age of marriage. The age of sexual consent means that the individual has the legal capacity to give consent for sexual activity, while the age of marriage refers to an individual is eligible to enter a social and legal marriage contract (UNFPA, 2020).

Historically, many countries assigned the age of consent according to the age of puberty for girls, however with increasing awareness of child exploitation, many countries have increased the age to consent to protect children from exploitation. The protection aspect recognizes that children sometimes lack the knowledge, power or means to give informed consent (Petroni et al., 2019). However, to deal with the protection aspect, most countries also have statutory rape laws, which criminalize sexual activities with children below the age of sexual consent. However, in many countries, including India, legal penalties for child marriage are not enforced by the state (Petroni et al., 2019). This inequity in the protection of children from sexual harm, emphasis the global inequality and normalization of institutional sexual harm in terms of marriage.

This also brings into focus that moralistic values like ‘chastity’ and ‘honour’ for girls before marriage also influence laws of age to sexual consent in many countries, including India. Such laws also contribute to restricting adolescents’ ability to explore their sexuality. The raising of the age of sexual consent to the age of marriage consent has essentially played into the normative patriarchal sexual control of women in India, increasing familial control and strengthening the regressive societal norms related to adolescents’ sexuality and marriages, as seen in the case example above.

Consensual Sexual Exploration – A Crime

After the implementation of POCSO, about 30% of cases in Delhi (S, 2014) and 23% of cases in Mumbai (S, 2015) registered under POCSO were stated as consensual by the girls in the court during the trial. Between the years 2013 and 2016, in the cities of Mumbai, Delhi and Lucknow, consensual sexual relations make up 18 to 54 percent of POCSO cases (Pitre & Lingam, 2022).

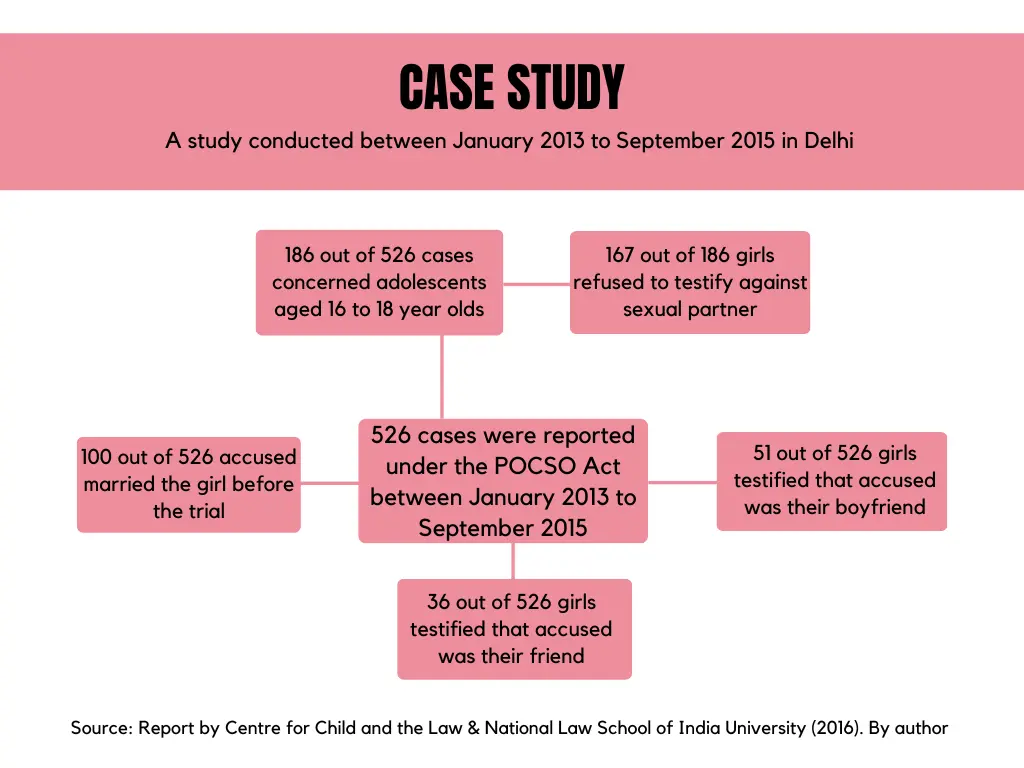

An overwhelming number of such cases are usually filed by the parents of the consenting girl. The below case study further explains the plight of Indian adolescents in consenting relationships.

A misuse of this law to curb teenage sexuality, leads to a burden on judicial stakeholders. The already overburdened courts dealing with consensual sexual relationships, which mostly lead to acquittal as the girls refuse to testify against their boyfriends, indicate the unreachability of resources to those really in need of justice. Trials of consensual sexual relationships is one of the factors leading to the failure of the implementation of the POCSO Act.

Apart from the POCSO mandate, the Criminal Procedure Code of 1973 also mandates hospitals to report all sexual offenses, failing to do so is a punishable offense by two years imprisonment. Many sexually active adolescents require access to varied healthcare services like contraception, treatment for STI/STDs, access to safe abortions, etc. However, mandatory reporting makes these healthcare services quite inaccessible to adolescents, as any sexual activity with anyone below 18 is a criminal offense. In 2019 abortion clinics reported a drop of 95% in girls below 15 years of age. There is a high probability that these girls are accessing undocumented places or unsafe practices, which can have a negative impact on their health (Pitre & Lingam, 2022). Healthcare providers have also refused sexual and reproductive health services to adolescent girls due to the mandatory reporting requirements (Pitre & Lingam, 2022). This is creating a severe health hazard for an already vulnerable population.

What are the solutions?

In a conservative society like India, it is definitely difficult to make room for adolescent sexuality. The societal norms are rigid, and when we add the fact that India still remains one of the unsafe countries in the world for women, the protection of children does become a strong priority. However, adolescents form about 20% of India’s population, and we need to make their well-being a priority as well. Having a safe environment for adolescents to explore their sexuality is not only their right, but also a psycho-legal responsibility, especially when it is heavily stigmatized culturally. The Ministry of Women and Child Development have the following options to address the concerns.

Amendment of the POCSO Act

Reducing the Age of Consent and adding ‘Romeo Juliet’ Clause

Globally, the median age for boys to have had their first sexual intercourse is 17.7 years, while for girls, it is 17.9 years (Petroni et al., 2019). This implies that more than half of adolescents globally are sexually active by the time they reach the age of 18. Indian statistics also suggest that 39% of adolescents have had sex before the age of 18 (Pitre & Lingam, 2022). The criminalization of consensual sexual exploration until 18, is at this point unrealistic.

The high age of sexual consent in India is not only impacting adolescents’ right to their sexuality and agency to make choices about their sexual partners, but also their health leading to health hazards that we are statistically blind to. The current age of sexual consent is also a cause of heavy burden on the legal system, making justice delayed for children who have been sexually harmed.

The age of sexual consent needs to be congruent with the developmental needs and rights of adolescents. As the law currently stands, adolescents do not have any rights to sexual exploration. However, POCSO makes this exploration a criminal offense.

The first recommendation to the MWCD would be to amend the POCSO Act to reduce the age of sexual consent. The recommendations for a new age of sexual consent:

(a) consensual non-penetrative sexual exploration between children above the age of 13 years, having a maximum of 2 years of age gap

(b) consensual penetrative sexual exploration between adolescents above the age of 16 years, with a maximum age gap of 3 years.

The allowance of non-penetrative sexual exploration for adolescents older than 13 can also decriminalize consensual sexual exploration. This might in effect, reduce the burden on courts of cases which are not under the umbrella of harm. This will also reduce the girls’ parents from reporting the boy under POCSO in an effort to maintain their honour.

Reducing the age of sexual consent to 16 years will allow hospital employees to give healthcare access to adolescents, addressing the health hazard, as consensual sexual activities wouldn’t be criminalized. This may reduce the barriers for many adolescents to access protection, in case of sexual harm, as the hospital staff and private citizens will be able to better understand the adolescent’s side of the story.

The addition of close in age clause is further recommended to prevent adults from grooming, or exploiting adolescents even if they are of consenting age. Many countries like France (minors of 15 years and an individual up to five years older) and other countries have a similar provision acknowledging children’s sexual exploration in consensual relations.

Setting up of Child Services

Mandatory reporting of sexual offenses ensures that children getting abused have access to medico-legal support as soon as possible. However, one of the strongest critiques of POCSO is the law enforcement’s attitude towards most child sexual abuse cases, especially when the case is of consensual sexual relations. Mandatory reporting by healthcare professionals though important to address cases of sexual abuse and assault. In the case of adolescent consensual sexual exploration, it leads to the inaccessibility of healthcare.

The critiques of mandatory reporting can be addressed by making a provision for mandatory reporting to a Child Services team, which can be set up under the Aftercare part of POCSO. The Child Services are sensitized to understand the difference between consensual and non-consensual relations as well as coercive and consensual relations. They would then further report the cases of actual hard to law enforcement. This will not only lead to a reduction in cases of consensual sexual relations being taken to courts, but also ascertain those adolescents aren’t coerced to have sexual relations.

Child Services would then further file a report with law enforcement if the child reports harm. However, no further reporting would be necessary if there is no harm found and consent is freely given.

Conclusion

The Madras High Court and Calcutta High Court (The Print, 2022) have pointed out that the law is in place to protect children from violence and harm. The use of it to penalize adolescents for exploring sexuality would be a draconian interpretation of the law that would amount to an abuse of the law. To address these grey areas of the law and to make it more adolescent-rights-friendly, an efficient amendment of POCSO is necessary. Though there is a long way to go, the above recommendations are definitely culturally appropriate and sustainable in the long term making it safer for adolescents.

Cover photo courtesy The Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society, La Trobe University

Bibliography

Anchan, V., Janardhana, N., & Kommu, J. V. S. (2021). POCSO Act, 2012: Consensual Sex as a Matter of Tug of War Between Developmental Need and Legal Obligation for the Adolescents in India. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 43(2), 158–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/0253717620957507

Centre for Child and the Law & National Law School of India University. (2016). A report of the study on the working of special courts under POCSO, 2012 in Delhi. https://acrobat.adobe.com/link/review?uri=urn:aaid:scds:US:29a3e2d8-11f0-4e55-9c6a-98a9840f8a35#pageNum=1

Implementation of the POCSO Act 2012 by Special Courts: Challenges and Issues. (2018). https://ccl.nls.ac.in/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Implementation-of-the-POCSO-Act-2012-by-speical-courts-challenges-and-issues-1.pdf

Petroni, S., Das, M., & Sawyer, S. M. (2019). Protection versus rights: Age of marriage versus age of sexual consent. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 3(4), 274–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30336-5

Pitre, A., & Lingam, L. (2022). Age of consent: Challenges and contradictions of sexual violence laws in India. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters, 29(2), 1878656. https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2021.1878656

Renu, R., & Chopra, G. (2019). Child Sexual Abuse in India and the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act 2012: A Research Review. Integrated Journal of Social Sciences, 6(2), 49–56.

S, R. (2014, July 29). The many shades of rape cases in Delhi. The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/data/The-many-shades-of-rape-cases-in-Delhi/article60437026.ece

S, R. (2015, December 22). Why the FIR doesn’t tell you the whole story. The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/rukmini-s-writes-about-the-mumbai-sessions-court-rulings-on-sexual-assault-during-2015-why-the-fir-doesnt-tell-you-the-whole-story/article8014815.ece

Suresh, N. (2022). India: Calls to lower age of consent to 16 over teen romance – DW – 12/29/2022. Dw.Com. https://www.dw.com/en/india-calls-to-lower-age-of-consent-to-16-over-teen-romance/a-64237659

The Print. (2022, February 15). How courts are ‘creatively interpreting’ grey zone between minors & consent in POCSO cases. ThePrint. https://theprint.in/opinion/how-courts-are-creatively-interpreting-grey-zone-between-minors-consent-in-pocso-cases/832026/

UNFPA. (2020, November 27). Technical Brief: Harmonization of Minimum Ages and Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights. UNFPA ESARO. https://esaro.unfpa.org/en/publications/technical-brief-harmonization-minimum-ages-and-adolescent-sexual-and-reproductive

About the author

Anushree Dirangane is an experienced trauma-informed psychologist from India, who has worked in the area of child sexual abuse and trafficking. Anushree has also worked in the area of public health in Uganda. She is currently a candidate in the MPP program, specializing in Global Public Policy and Socio-economic Developmental Policies.

~ The views represented in this blog post do not necessarily represent those of the Brandt School. ~