Rob Peter to Pay Paul: The Indonesian Fintech Lending Dilemma

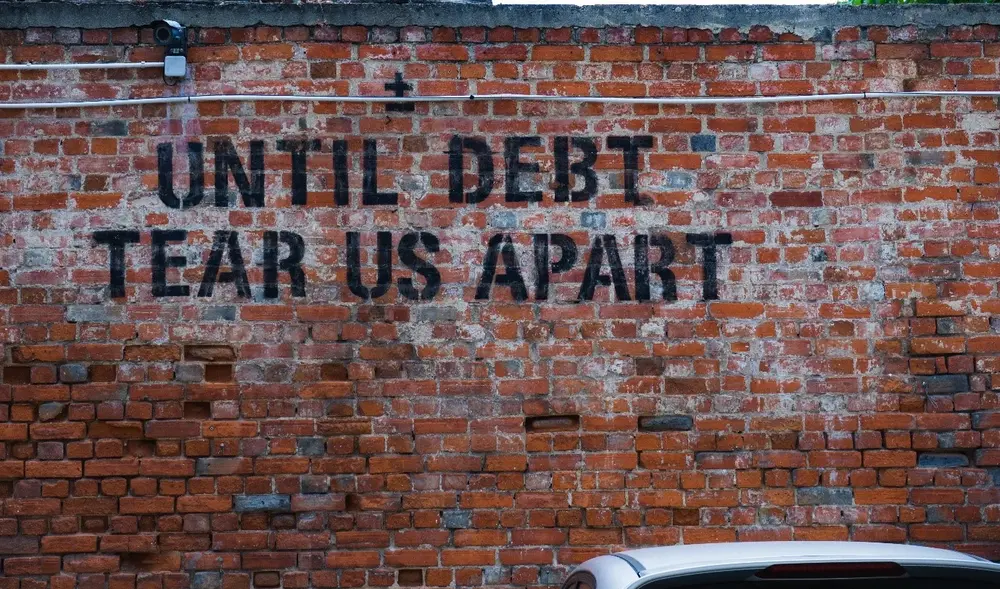

There is a well-known idiom attached to money or debt situations called “rob Peter to pay Paul”. The phrase simply means someone is taking money wrongfully to pay off a debt. In Indonesian, there is the same phrase: "Gali Lubang Tutup Lubang" (in English: dig hole to cover the other hole). But why is this even established in several languages? Why would we rob Peter in the first place?

The Increasing Trend of Indonesia Financial Inclusion

In October 2020, Indonesian President, Joko Widodo, announced an ambitious goal which aimed to achieve broader financial inclusion in the country. The government set a goal of 90% inclusion for people in Indonesia to be financially included by 2024. However, with such levels of inclusion in an advanced system and infrastructure, can society properly take advantage of this development and are they making sound money decisions?

According to the World Bank, financial inclusion is becoming a fundamental part of the Sustainable Development Goals. It also showed that more accessible access to finance will reduce severe poverty and improve overall prosperity (World Bank, 2022). With optimum financial inclusion, it will help governments to provide citizens better access to savings, investments, and other financial products in a sustainable and responsible way. Today, Indonesia's financial inclusion is impressively developed, with digitalization having boosted user engagement. According to a report published by the Indonesia Financial Service Authority (Otoritas Jasa Keuangan or OJK), the levels of financial inclusion in 2022 grew to 85.10% (Otoritas Jasa Keuangan [OJK], 2022).

The Gap between Financial Inclusion and Financial Literacy

Unlike financial inclusion, the current level of Indonesian financial literacy is still 49.68%, which compared to the financial inclusion rate has left a disparity of 35.42 % (OJK, 2022). It means that although the system is well prepared and provided, users may have a low understanding of the products they utilize. Since financial institutions have thousands of financial products, the decisions are getting more complicated. People need a higher level of knowledge to benefit from them (Dewi et al., 2020; Panos & Wilson, 2020).

Based on OJK reports, one of the financial products with the lowest financial literacy is Financial Technology Lending (Fintech Lending), which has raised concerns due to its increasing inclusion and usage. Fintech lending has the second worst financial literacy rates with only 10.9% literacy in 2022 (OJK, 2022a). At the same time, the expansion of internet access is assisting in the growth of fintech transactions. In 2022, 1 out of every 21 Indonesian teenagers (< 19 years old) already had a fintech loan, indicating that the younger generation has more open and earlier access to debt than the older generations (Chantarat et al., 2020; Indonesia Internet Service Provider Association, 2022). However, given the poor level of financial literacy on these fintech products, did the society especially younger generation borrow money wisely and could this severely effect their future?

Impact of the Inadequate Financial Literacy

Fintech does help households by increasing consumption through borrowing. This enables them to stretch their budget with more flexible and faster financing services for purchasing foods and goods. But these households often spent more than they can afford and borrow more than they can pay back. This puts them in a Non-Performing Loan (NPL) situation, in which the loan repayment is late or impossible (Agarwal & Chua, 2020).

By November 2022, the total NPL in fintech lending exceeded IDR 1,425 billion (USD 91 million). In other words, there are almost three times more loans compared to the beginning of the year that will that are classified as NPLs (Otoritas Jasa Keuangan, 2022a). The NPL growth should be addressed since the explosive consumption financed by debt with a lack of financial knowledge will bring over-indebtedness, economic instability and vulnerability in the household (Andersen et al., 2016; Cardaci, 2018; Hidajat, 2020).

In Indonesia, those with many NPLs are primarily from low and middle-income families. Only about 10% of households have saved enough to cover their basic living expenses for more than a year, whereas almost 80% have savings that are hardly enough to cover basics for less than a month (Noerhidajati et al., 2021). If the loans remain unpaid this will lead them to "rob Peter to pay Paul”. In this practice, individuals take out a new loan from the fintech platform to pay off their debt in other platforms until they realize the debt is too big and cannot repay it. One borrower took out loans from 168 fintech institutions, totalling up to IDR 200 million (USD 13,000) (Herdiansyah & Himawan, 2022).

As the situation worsens, some borrowers are affiliated with illegal financial institutions, and the terror produced by illegal lenders exacerbates the situation. In 2018, more than a thousand cases of illegal loans were reported to the Jakarta Legal Aid Institute (Lembaga Bantuan Hukum Jakarta) (Pramono, 2018). Those cases involved borrowers conducting humiliating activities that affected both material and mental stability, resulting in suicide attempts, divorce and job termination due to depression and social pressure (Dew, 2011; Richardson et al., 2013; Turunen & Hiilamo, 2014).

The Urgency of More Efforts to Raising Financial Literacy

Currently, the financial literacy program is regulated by OJK, under Law Number 21 (2011), which is responsible for providing education on financial products to the public. There are already several financial literacy programs taking place. However, the current programs do not perfectly resolve the fintech debt trap problem.

Despite the program already being rolled out, according to research by the Center for Indonesian Policy Studies (CIPS), most Indonesian financial literacy programs focus on promoting financial institutions' products rather than managing spending through the financial product (Suleiman et al., 2022). And in terms of program content, the financial literacy delivered predominantly concerns savings.

A specially tailored program such as debt literacy instead of financial literacy will engage those who seek information about debt more so than financial literacy in general (Cwynar et al., 2019). Debt literacy could help those who often pay only the minimum monthly loan, those who pay late and spend over-the-limit (Lusardi & Tufano, 2015). Although the fintech loan contract agreement contains information on loans and the terms and conditions, the user is unlikely to understand entirely.

Apart from that, educating citizens on financial literacy should not only provide financial products information. Financial education could also mean providing skills to adapting emotional capacities during financial transactions (Pettersson & Wettergren, 2021). The current financial literacy agenda is more familiar to those not participating in financial activities. While those already indebted are often neglected, which does not mean they are necessarily financially literate.

Notwithstanding, there will be a trade-off associated with this effort. Indonesia's expected rise in the fintech industry may be hampered by increasing debt awareness in society. It may have an impact on the fintech lending companies and their employees. Thus, it could result in the inefficiency of economic sectors and unemployment.

But nonetheless, the question is, until when should we rob Peter? Maybe Peter is not only another fintech platform, but it could also be our time, physical and mental health that we should not rob but protect instead.

Cover photo courtesy of Ehud Neuhaus

References:

Agarwal, S., & Chua, Y. H. (2020). FinTech and household finance: A review of the empirical literature. China Finance Review International, 10(4), 361–376. doi.org/10.1108/CFRI-03-2020-0024

Andersen, A. L., Duus, C., & Jensen, T. L. (2016). Household debt and spending during the financial crisis: Evidence from Danish micro data. European Economic Review, 89, 96–115. doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2016.06.006

Cardaci, A. (2018). Inequality, household debt and financial instability: An agent-based perspective. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 149, 434–458. doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2018.01.010

Chantarat, S., Lamsam, A., Samphantharak, K., & Tangsawasdirat, B. (2020). Household Debt and Delinquency over the Life Cycle. Asian Development Review, 37(1), 61–92. doi.org/10.1162/adev_a_00141

Cwynar, A., Cwynar, W., & Wais, K. (2019). Debt Literacy and Debt Literacy Self-Assessment: The Case of Poland. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 53(1), 24–57. doi.org/10.1111/joca.12190

Dew, J. (2011). The Association Between Consumer Debt and the Likelihood of Divorce. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 32(4), 554–565. doi.org/10.1007/s10834-011-9274-z

Dewi, V. I., Febrian, E., Effendi, N., Anwar, M., & Nidar, S. R. (2020). Financial Literacy and Its Variables: The Evidence from Indonesia. Economics & Sociology, 13(3), 133–154. doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2020/13-3/9

Herdiansyah, M. F., & Himawan, K. K. (2022). Escaping the “devil’s trap”: Exploring the role of online social support for fintech lending’s over-indebted Indonesian customers. International Social Science Journal, 72(245), 769–785. doi.org/10.1111/issj.12348

Hidajat, T. (2020). Unethical practices peer-to-peer lending in Indonesia. Journal of Financial Crime, 27(1), 274–282. doi.org/10.1108/JFC-02-2019-0028

Indonesia Internet Service Provider Association. (2022). Indonesian Internet Profile 2022. APJII.

Lusardi, A., & Tufano, P. (2015). Debt literacy, financial experiences, and overindebtedness*. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 14(4), 332–368. doi.org/10.1017/S1474747215000232

Noerhidajati, S., Purwoko, A. B., Werdaningtyas, H., Kamil, A. I., & Dartanto, T. (2021). Household financial vulnerability in Indonesia: Measurement and determinants. Economic Modelling, 96, 433–444. doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2020.03.028

Otoritas Jasa Keuangan. (2022a, October). Financial Technology Lending Statistic—November 2022 Period. www.ojk.go.id/id/kanal/iknb/data-dan-statistik/fintech/Pages/Statistik-Fintech-Lending-Periode-November-2022.aspx

Otoritas Jasa Keuangan. (2022b, November 22). Press Release: National Survey on Financial Literacy and Financial Inclusion 2022. www.ojk.go.id/id/berita-dan-kegiatan/siaran-pers/Pages/Survei-Nasional-Literasi-dan-Inklusi-Keuangan-Tahun-2022.aspx

Panos, G. A., & Wilson, J. O. S. (2020). Financial literacy and responsible finance in the FinTech era: Capabilities and challenges. The European Journal of Finance, 26(4–5), 297–301. doi.org/10.1080/1351847X.2020.1717569

Pettersson, J., & Wettergren, Å. (2021). Governing by emotions in financial education. Consumption Markets & Culture, 24(6), 526–544. doi.org/10.1080/10253866.2020.1847720

Pramono, A. M. (2018, December 9). Trapped in Online Lending, 1330 Victims Report to Jakarta Legal Aid Institute (Terjerat Pinjaman Online, 1330 Korban Mengadu ke LBH Jakarta). LBH Jakarta. bantuanhukum.or.id/terjerat-pinjaman-online-1330-korban-mengadu-ke-lbh-jakarta/

Richardson, T., Elliott, P., & Roberts, R. (2013). The relationship between personal unsecured debt and mental and physical health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(8), 1148–1162. doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2013.08.009

Suleiman, A., Dewaranu, T., & Anjani, N. H. (2022). Creating Informed Consumers: Tracking Financial Literacy Programs in Indonesia. repository.cips-indonesia.org/publications/358319/

Turunen, E., & Hiilamo, H. (2014). Health effects of indebtedness: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 489. doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-489

World Bank. (2022, March 29). Financial Inclusion. World Bank. www.worldbank.org/en/topic/financialinclusion/overview

About the author

Novita Andari is a first-year student of Master of Public Policy at the Willy Brandt School. Before coming to Germany, she worked as a Tax Officer in one of Indonesia’s State-Owned Company. She is particularly interested in finance, tax and fiscal policy.

~ The views represented in this blog post do not necessarily represent those of the Brandt School. ~