Why COVID-19 Will Increase Automation Anxiety

Technological revolutions have always created the fear of mass unemployment and societal disruption. While the classic example in economics history is weavers losing their jobs to knitting machines in the early 19th century, we all know instances that are more contemporary: Kodak out of business due to the rise of digital photography or electronic payment systems that make tollbooth operators redundant. The list goes on.

Advances in digitalization and automation have increased the speed of technological transformation. Physical and virtual automation, building on artificial intelligence and machine learning, increasingly make jobs redundant that until now were considered safe. This concerns a wide range of unskilled and routine-based jobs within manufacturing, logistics and the finance business in high-income economies, and agriculture, manufacturing and retail in low- and medium-income economies (e.g. de Dieu Cirhigiri Kizito et al. 2020).

The current COVID-19 pandemic will speed up and intensify these changes. As lockdown-policies have led to lay-offs and introduced a global recession, the pandemic has made global mass unemployment a sudden reality. At the same time, while business activity is stalling, firm’s automation efforts are not. According to EY’s latest Global Capital Confidence Barometer, 36% of global executives were already taking steps to accelerate automation in March. Another 41% aimed to re-evaluate their speed of automation. Will these efforts end up displacing the recently lost jobs even beyond the pandemic, and for good?

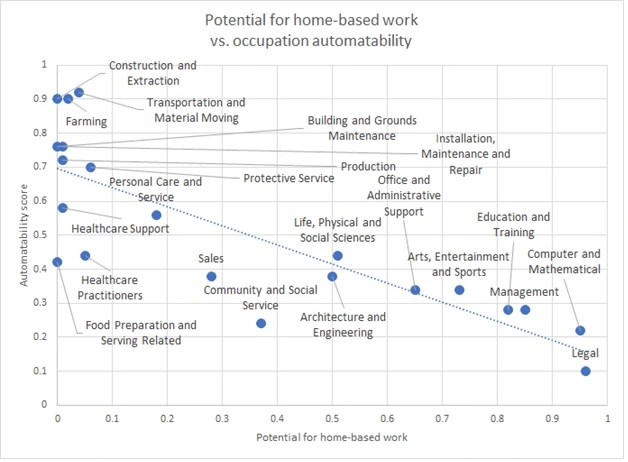

As an illustration, let us look at how automatable the occupations most affected by the COVID-19 crisis are. We draw on data from Vermeulen et al. (2018) on US occupations’ degrees of automatability, and Avdiu and Nayyar’s (2020) assessment of these occupations’ potential for home-based-work. Figure 1 plots these two variables against each other.

Figure 1 illustrates an inverse relationship between an occupation’s potential to be carried out from home and its potential to be automated and displaced. Lawyers or computer engineers are among those professions that seem to be neither easy to automate nor to depend on physical interaction. Both types of services can be delivered virtually and from home. On the other hand, logistics, construction and production are often routine-based tasks, and do require physical interaction with goods and customers. Other examples are precisely these kinds of jobs that our society currently praises the most: healthcare, retail and maintenance services.

Thus, occupations threatened by automation also tend to require face-to-face interaction. This suggests that the automation risk will become even bigger in the aftermath of the COVID-19 crisis. The fear of physical contact pushes companies, service centers and consumers to consider technology: online purchases, online classes, automated delivery and services. Healthcare and retail workers may be spared in the short run due to current public attention, but other, recently displaced jobs may not return after the crisis is over. The longer lockdowns are in place, the more likely will society include automation into what will then be considered a ‘normal’ life.

Hence, the next years will likely bring a surge of inequality and informality, for which all economies will need to find solutions. Automation anxiety is already prevalent in the minds of voters, and there is some evidence that policy makers respond to it (Gast Zepeda and Kemmerling fc.). The sooner civil society begins to discuss a desirable future of work, and the sooner governments begin to experiment with novel policy options, the more capable the economy will be to influence their fate. This includes capacities to steer towards an economy in which automation creates more jobs than it replaces. Entrepreneurship, lifelong learning, and the radical revision of education are key policy areas in this respect. Simultaneously, governments must deepen their capacities to absorb major job displacements, should these nonetheless happen. This would require improving public finances as well as universalizing social security to include informal and new job types. It might even challenge us to revisit our very notion of work and how we define valuable activities.

References

Avdiu, B., & Nayyar, G. (2020). When face-to-face interactions become an occupational hazard: Jobs in the time of COVID-19. Brookings Institution. Future development. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2020/03/30/when-face-to-face-interactions-become-an-occupational-hazard-jobs-in-the-time-of-covid-19/

de Dieu Cirhigiri Kizito, Jean ; Dutta, Kankana ; Fuentes, Consuelo ; Gul, Faiqua ; Hebel, Hendrik ; Adetunji Oyebamiji, Usman ; Santana Fano, Emma ; Santiago, Alyssa ; Volkmann, Stefan (2020): The Future of Work. Report to the Aspen Institute Germany. Brandt School Project Group Reports.

EY (2020). How do you find clarity in the midst of a crisis? Addressing the “now“ is critical, but anticipating the “next“ and “beyond“ is the optimal response to COVID-19. Global Capital Confidence Barometer March 2020, 22nd edition https://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/2020_GCCB/$FILE/Final%20report%20-%20CCB22.pdf

Gast Zepeda, S. & Kemmerling A. (fc.) Do we run out of jobs? in: Busemeyer, M. et al. (eds.) Digitalization and the Future of the Welfare State.

Vermeulen, B., Kesselhut, J., Pyka, A., & Saviotti, P. (2018). The Impact of Automation on Employment: Just the Usual Structural Change? Sustainability, 10(5), 1661. doi.org/10.3390/su10051661

Authors:

Prof. Dr. Achim Kemmerling is the Gerhard Haniel Professor for Public Policy and International Development and the Director of the Brandt School since April 2019. He is the Coordinator of the research cluster “Development and Socio-Economic Policies“.

Stefan Volkmann is currently a Master of Public Policy candidate at the Willy Brandt School of Public Policy. He builds on an academic background in library and information management. He has work experience in NGO management, public sector consulting, and audit.

Stephanie Gast Zepeda is a Ph.D. student and research assistant to the Gerhard Haniel Professor for Public Policy and International Development at the Willy Brandt School of Public Policy. She holds a B.A. in International Cultural and Business Studies from the University of Passau and an M.A. in International Political Economy from King’s College London.

“The views represented in this opinion piece do not necessarily represent those of the Willy Brandt School of Public Policy.”

~ The views represented in this blog post do not necessarily represent those of the Brandt School. ~